Happy Easter...Antique Cards Digitized! Many of us collect Reward of Merit Cards, those quaint little gift cards teachers awarded to students for their fine schoolwork. We often find them tucked among the ephemera in antique stores and marvel at the Spencerian script of the teachers who spent their own pennies to acknowledge the dedication of their scholars with hand-written praise. Thumbing through postcards and old photos you may also come across a collection of early 2oth century Easter cards, more prevalent than you might think. Even then people related Easter with bunnies, flowers, chicks, candy, and eggs as the artwork shows. So when and why did these symbols of Easter emerge? Some surprising information below! Not to reinvent the wheel here, it's better if I can point you to two fascinating resources that are both visual and informational. Digital Easter Cards 1. The first link is a set of 270 digital scans of early Easter cards, some with rhyme, from the New York Public Library Digital Collections. Click on the gray image above to access card collection. Scroll down to where you see the image above and click on: "View as book.." Use the forward arrows in the right lower corner to view all 270 cards. Have fun! Symbols and Traditions of Easter 2. An article from the History Channel March 19, 2024 (second printing) that explains the where, when, and why these Easter symbols and traditions emerged. They encourage SHARING! Here's the direct link: https://www.history.com/topics/holidays/easter-symbols BTW...Happy Easter!

0 Comments

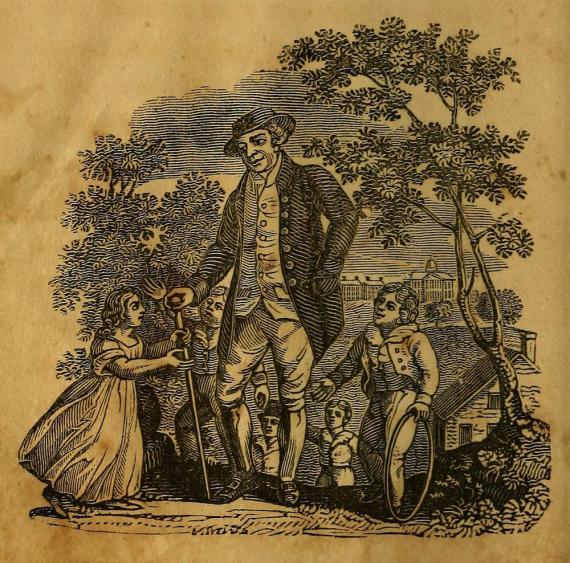

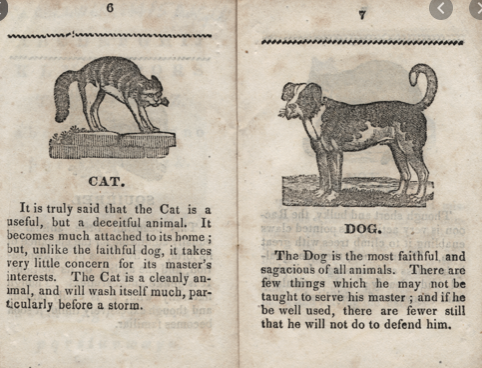

Samuel Griswold Goodrich, 19th Century Author Information from: Boston Public Library, Rare Books & Manuscripts, University of Washington Digital Collections In Ridgefield, CT stands the classic Little Red Schoolhouse known as the Peter Parley Schoolhouse, named in honor of its most famous student Samuel Griswold Goodrich. How is that you might ask? Samuel was born in Ridgefield, Connecticut, the 6th of ten children, the son of a minister, in 1793. He would attend this “Lane Street School” from 1799-1803. You may already be familiar with Pater Parley's tales. But it was Samuel Goodrich who entered the world of book publishing in 1816 at the young age of 23. In the early 1820s Goodrich came to the conclusion that children as well as adults preferred to read truth rather than fancy and that it would be possible to present truth--history, geography, science, etc.-- in such a way that it would be more interesting to children than fairies, giants and monsters. So, he became a publisher and writer of children’s books. In 1827, Samuel Goodrich introduced his pen name character, Peter Parley, an elderly, quirky, but also lovable old Bostonian who enjoys telling stories to children. With his gouty foot and crooked hat, Parley introduced his first book for children entitled Peter Parley’s Tales About America. He became so popular that other children’s writers attempted to copy his likeness all over the world, but he could not fight the frauds. Goodrich is self-credited with writing over 170 books that sold over 7,000,000 copies and numerous periodicals, though he was clearly not the sole author. His 170 volumes told stories of history, geography, science, nature, animals, and people of the world. He wrote in short paragraphs while featuring black line engravings that captured the biographies of the famous and the little known. Many of Parley's "facts" were of questionable accuracy (Laplanders ask the advice of black cats, and Peter the Great once worked as a carpenter to learn how to build ships.) Interspersed with these "facts" is a liberal sprinkling of moral preaching. There were also evidences of Goodrich's prejudices and biases (These people are ignorant and superstitious.) The frontispieces of most of the books are portraits of the author in varying states of health. Although he is depicted as an older man he was in fact a young man in the 1820s and 1830s. He steered clear of fairy tales saying, “Common sense tells us not to take children into scenes of crime and bloodshed, unless we wish to debase them.” Goodrich was a fascinating character and the members of the Ridgefield Historical Society have created marvelous videos that tell the story in great detail. The Peter Parley Schoolhouse is curated by the Ridgefield Historical Society where docents tell stories about the charming schoolhouse and Peter Parley himself. For extensive information on the history of the school, Samual Goodrich (a.k.a Peter Parley), his works, and the preservation of the Peter Parley Schoolhouse, visit the link below and the wonderful RHS videos. (2 parts) Things We Probably Never Knew!

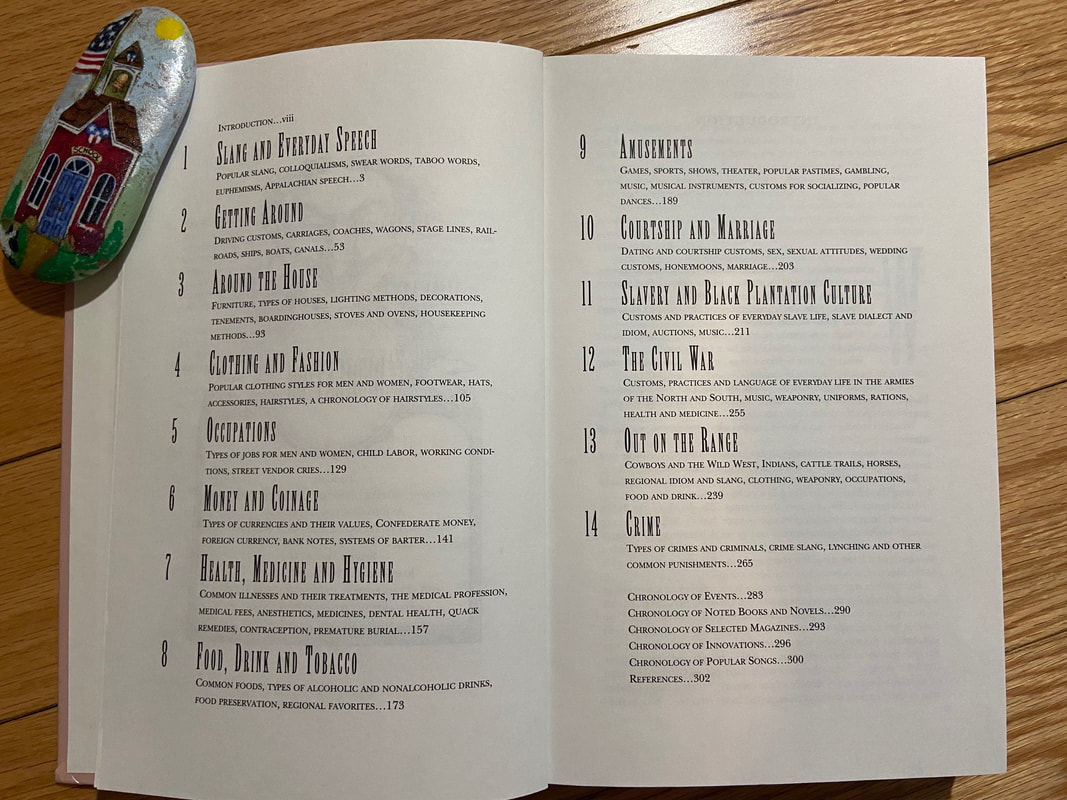

If you curate a schoolhouse you’ve undoubtedly worked to piece together its history beyond the date it was built or closed. In your search you’ve most likely relied on scant existing records, superintendent’s annual reports, personal narratives, lists of students and teachers, and whatever photos you are fortunate to locate. We all take pride in locating information that will bring our schoolhouse to life. But here’s a resource that can bring the actual era of your schoolhouse to life through the language and customs of the time! Available for short money as new or used books on Amazon these, “Writer’s Guides To Everyday Life in…,” are fun, informative, and fascinating trips through 18th, 19th and 20th century daily life. (Be sure to check out “used” editions on Amazon, Alibris, or Abebooks.) Use them to enhance your schoolhouse stories, make your audiences laugh, surprise your listeners, and fact check society during your school’s existence. These books are not expansive histories like high school textbooks or scholarly tomes. Instead, they offer hundreds of pages of surprising definitions, engaging explanations, and delightful vignettes about the times they cover. As a bonus, the chronologies and source references in the index are priceless! As an example, check out the photo below to explore the many topics covered in The Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life in the 1800’s….and have some fun! Just a suggestion. Help! What do we need to get started? Recently, I was contacted by two New England towns who are restoring their schoolhouses and would like to open them eventually for young visitors, 3rd or 4th grades. Their dilemma was finding out what artifacts and materials they would need to stage a schoolhouse for atmosphere and what lessons would be taught during chosen time periods. Having visited hundreds of schoolhouses during CSAA conferences, personal searches, and surprise encounters along the road, the list of possibilities got mighty long. We enthusiasts have seen beautifully preserved collections that probably took years to amass. Many of these restored and staged country schools turn us green with envy or send us out on a mission of self-improvement in our own schools. The artifacts like slates, original school desks, teacher bells, period toys, and pencil boxes, etc. are becoming more scarce as the new preservationists join the search. It also depends on what era you intend to re-live during the years your schoolhouse was open. Fortunately, both preservationists I spoke with were restoring schools from the 1840's and I had been collecting for many years 1800's appropriate items. Sometimes I have to settle and "get as close as I can," to what is authentic or time sensitive, not always with success. To help out initially, I drew up a list of antiques, reproductions, or sources that could get them up and running toward programming, and shared with them a simple two-hour lesson plan. (NOTE: I'd also like to collect your daily schedules for a special sharing resources page on the CSAA website.) These are the times that CSAA can help the most. New schoolmarms/masters think we're all geniuses at the CSAA and that we have all the answers. Not all, but we have a LOT of them! Collectively, we have endless ideas that we could share with those adrift in their programming. In The Report Card editions ahead, I will post programming ideas from the 2021 Virtual CSAA Conference (virtual because of COVID). Our presenters created video slide shows of their schools, many of which have descriptions of their programs. We thank them in advance! For this post, I will share a list of items I suggested to my two new friends to help them on their way to staging their 1840's schoolhouses with affordable and useful supplies. STARTER KIT LIST: CLICK ON THE PICTURE COLLAGE AT THE TOP OF THIS POST! Your suggestions would be MOST WELCOME to add to this list especially if your school post-dates the 1840's. (Big Chief tablets, dictionaries, pencil sharpeners, flash cards, crayons, water color paints, paste jars, etc.). Make your own list and submit it here! s[email protected] The Report Card welcomes your input and we're always looking for interesting articles, by YOU.... Thank you, Susan Fineman The Ideals of Patriotism by William Backus Guitteau, Toledo, OH Native, Historian, & Author. (1917) Patriotism, the greatest of our national ideals, comprehends all the rest. Love of country is a sentiment common to all people and ages; but no land has ever been dearer to its people than our own America. No nation has a history more inspiring, no country has institutions more deserving of patriots love. Turning the pages of our nation's history, the young citizen sees Columbus, serene in the faith of his dream; the Mayflower, bearing the lofty soul of the Puritan; Washington girding on his holy sword; Lincoln, striking the shackles from the helpless slave; the Constitution, organizing the farthest west with north and south and east into one great Republic; the tremendous energy of free life trained in free schools; utilizing our immense natural resources, increasing the nation's wealth with the aid of advancing science, multiplying fertile fields and noble workshops, and busy schools and happy homes. This is the history for which our flag stands; and when the young citizen salutes the flag, he should think of the great ideals which it represents. The flag stands for democracy, for liberty under the law; it stands for heroic courage and self-reliance, and the cause of humanity; it stands for free public education, and for peace among all nations. When you salute the flag, you should resolve that your own life will be dedicated to these ideals. You should remember that the truest American patriot understands the meaning of our nation's ideals, and pledges his/her own life to their realization. From the Patriotic Reader, Houghton Mifflin Company (1917) Note: As a schoolmarm in a country school museum for the past 18 years I am thrilled when students demonstrate great enthusiasm for patriotism and love of country. It reminds me of my public school teaching days when enjoying patriotic songs and stories was a regular exercise. Here I pay tribute to visitors to our schoolhouse from the Trinity Christian School in Concord, New Hampshire who sang proudly of our great flag and country. Enjoy their rendition of "America." I appreciate their enthusiasm even more as I find my own city's 4th grade visitors are unfamiliar with this classic..I see it. I feel it. Eighteen years ago they all knew it. Tell me about your current experience...comment below.  The Little Red Schoolhouse: Why? You find countless references to the Little Red Schoolhouse as preserved museums, in history, literature and lore. A web search of Little Red Schoolhouse yields hundreds of photos of little red schoolhouses. The reference is vivid, conjuring our image of what people imagine as the typical one-room school. However, we know that country schools were built of logs, brick, stone, wooden clapboard, adobe and sod, painted white, yellow, green, blue or often left unpainted. The question may be asked....why were so many painted red? One interesting explanation came to us as a reply to our YouTube video, "One-Room Schools of the Past." The writer commented: "A lot of schools were red in color for the same reason a lot of barns were red: because the railway companies would carry their own red paint to paint the cars, signs and cabooses of the trains on the rails across North America. The trains would carry so much of this "Red Lead" (lead oxide) paint that it was not only cheap, but readily available all along the railways (other paints were not so cheap or available). In the 1800s, "white paint" was mostly lime, chalk and water (whitewash), that would last a year at best on exterior surfaces. The other alternative was white paint made from white lead (lead carbonate) and boiled linseed oil, which was more expensive and less available than the railroad's red lead paint. From-Ronray.com ( site no longer available) Another informative answer to the question comes from a book entitled, "Requiem for the Little Red Schoolhouse," by Gerald J. Stout. I quote the passages below in the hope that you scout out an edition of his 1987 paperback that is rich in information about the country schoolhouse experience. The book was published by Athol Press. “Why red? The original pioneer schools, those which were built of hewn logs with cracks plastered with clay, were not painted at all... It was not until men began building houses, barns and schoolhouses of sawed boards, most commonly placed vertically and the joints covered with battens, that they began painting them to give color and protect wood from the ravages of time. Most old-timers of northeastern United States remember from their grandfathers that little red schoolhouses were as common as red barns, at least wherever they chose to paint them at all. Yet by my time, our Evans School was painted white as was the nearby school, White Dove, where my mother went to school back in the 1880's. The red schoolhouse era must go back to about Civil War time or shortly after log buildings were phased out and sawed weatherboard siding came into vogue. We have no direct evidence about the red color other than what took place with respect to farm barns, especially in eastern Pennsylvania. In that region the red barn is still common, even on modern farms where board fences and homes, unless made of brick are almost always painted white. In early days there was no scarcity of iron ore even in quite early days and relics of old iron furnaces are preserved in many places of Pennsylvania. When iron ore- or iron oxide- was ground fine, it could be used as pigment generally called venetian red. This was the inexpensive red coloring used in barn paint. One "vehicle" (liquid) into which iron oxide pigment was mixed was none other than buttermilk. The casein served in the same way it does in so-called water based paints of today. Eventually the United States obtained its own lead supply (rather than importing it) and the price dropped accordingly so white lead (lead oxide) could be used for painting the Cape Cod cottages of New England and farmhouses elsewhere. The most logical reason to explain why in later years schoolhouses came to be painted white rather than red, after white paint became cheap, is the idea that a schoolhouse should be painted like a house- it didn't seem quite right to paint a school like a barn." .....Gerald Stout NOTE: This article is a reprint from our original CSAA newsletter, but with added commentary. Stout's book is nearly impossible to find on-line anymore. Let us know if you get lucky! |

Our early public schools systems were indeed disparate, but a common thread among early districts was that children of all ages were taught together in the one-room schoolhouse" Blog Archives

July 2024

|